|

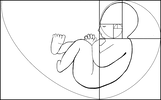

Birth and breast/chest feeding have been a part of history since the dawn of mammalian existence, bringing various species of mammal together in a profoundly simple, empathetic way. After all, what nursing parent can look upon a nursing lioness without a primal, instinctive understanding of the weariness in her eyes, or give a knowing smile when she pushes an overly rambunctious cub off her nipple after they get too rowdy? The birth and feeding of our young is simply a universal experience across species of mammals throughout the world. The longevity of our species is due to this process being incredibly efficient and it allows mammals to adapt to a plethora of sub-optimal environments. There is no doubt that the medical establishment has helped our population explode from 1 billion around the year 1800 to almost 8 billion today, just 1200 years later (Worldometer, n.d.), with the evolutionary big bang that is modern western or allopathic medicine. While there is no debate that the rise of allopathic medicine has dramatically improved maternal and infant mortality rates throughout the world, these life phases are never without risk. Due to the inherently vulnerable nature of birthing parents and their children, in 1948 the newly founded United Nations deemed these cohorts have the natural, inalienable right to specialized care and support. The nature of that care and support, however, has not been specified and as a result our species continues to face too many preventable maternal and infant deaths throughout the world. This paper will focus on the United States specifically as a relatively wealthy, developed nation as the challenges in developed nations are quite different than those in developing nations having already successfully overcome many of the challenges that developing nations continue to face regarding access to safe homes, clean water and basic medical care, for example. Rights of Birthing Parents and Children Who Need to Eat In the year 1924, the League of Nations adopted the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, which outlined some basic human rights for children throughout the world. These rights indicated that all children need the means for material and spiritual development, food when they are hungry, healthcare when they are sick, habilitation if they are disabled, rehabilitation if they are delinquent, given shelter and care if they are orphaned, protected from exploitation, the first to receive aid in times of distress, and raised to believe in the goodness of public service. Of course, like all other declarations of human rights the Geneva Declaration was merely a recommendation for policy, but not policy itself. In time it became clear to the newly formed United Nations that beyond their Declaration for Human Rights (1948), there was the need for a Declaration of the Rights of the Child and so this was published in 1959. It was then that the rights of the child grew to include an upgraded right to “adequate” medical services, protected from cruelty, neglect, and exploitation as well as special care and protection for children and their birthing parents that included “adequate” pre -and post-natal care. After the international marketing of artificial infant milks became overtly predatory, the World Health Organization created the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes in 1980. While that recommendation was made, the United Nations was working on a longer document which specified further rights for children and in 1989 the Convention on the Rights of the Child was ratified by many member-countries. In particular, this convention stated that all public or private institutions that undertake any action concerning children maintain the best interests of the child, that the rights of their parents or legal guardians be taken into account, that those institutions adhere to the standards that have been established by competent authorities regarding health, safety, and adequate staffing/supervision (Article 3), that children have the right to enjoy “the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health,” and that they are not deprived of their right to access such services, that nations take “appropriate measures” to decrease infant and child deaths, provide primary health care strategies, provide nutritious foods and clean water to drink, that families receive basic education in ideal nutrition, health, hygiene (physical and environmental), the prevention of accidents and “the advantages of breastfeeding” as well as anticipatory healthcare guidance regarding family planning (Article 24). Further, nations are expected to protect children from economic exploitation that may adversely impact their education, health, mental, physical, moral, social, or spiritual development (Article 32) and from any other form of exploitation adverse to their welfare (Article 36). The United States has signed some of these documents but has yet to ratify any of them. The Evolution of Birthing Norms in the United States Births have been attended by midwives for millennia. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, however, physicians came to be regular birth attendants in part due to their invention of the life-saving tool called the forceps— a tong-like device used to extract a baby who is not descending through the birth canal successfully, thus minimizing the risk of death for both the infant and the birthing parent (Kaplan, 2012)—and also due to their ability to provide pharmaceutical pain management for birthing parents in hospital settings. In the early 20th century, hospitals realized that supplemental birth interventions were financially lucrative and interventions such as intravenous line placement, epidural or spinal anesthesia, labor inductions or surgical births came to be much more common—as low-intervention natural births were not nearly as financially profitable (Leggitt, 2016). With increased urbanization and mobility of Americans during the 20th century, the idea of birthing in a hospital where nurses and attendants would tend to their every need was appealing (Kaplan, 2012). However, not all these promises led to positive results. The pain management physicians offered was called “twilight sleep” for birthing people; a combination of opioid narcotics and another medication which induced euphoria and amnesia that was all the rage after its introduction to obstetric care. Twilight sleep allowed parents to experience reduced pain during labor and birth, and to not remember much (if any) of the experience. Introduced in 1902, it was not until the mid-1960s that this medical cocktail fell out of favor due to its grave side effects on the baby’s central nervous system as well as on the emotional state of the birthing parent from having not fully witnessed their birth (Shiel, 2018). These side effects lead to the death of numerous infants and persistent emotional trauma for countless parents. Parents who did not have the opportunity to benefit from the surge of oxytocin (also known as the love or bonding hormone) which results from birth found that they were less emotionally connected with their infants than their peers who had not had this medication cocktail. It is not surprising that the advice to allow upset infants perceived as keen to manipulate their parents to cry it out, as written originally in Dr. Emmett Holt’s book The Care and Feeding of Children, came to be popular. Indeed, if parents found themselves to be less emotionally connected with their infants, then they’d have found their central nervous systems to be fully separate from that of their infants, then it would be much easier to separate themselves emotionally from their babies. Parents who have nursed their children directly know this separation to be easier said than done, as most experience a tangible physical sensation when their babies are upset with an instinctive need to calm them that cannot be quelled with any amount of logical self-talk. Dr. Holt’s book was copywritten in 1894, and again several times through 1907 (Project Gutenberg, 2007). This advice held dominance in the public eye until the opposite advice of nurturance and attentive love was given by Dr. Spock in his book Baby and Child Care (1946), after which time it is regarded to be one of the best-selling books of its century. Perhaps not coincidentally, Dr. Spock’s advice grew to fame around the same time that twilight births were on the decline and parents were beginning to once again experience the biologically normal surge of hormones which encourage emotional connectedness with their babies. What parents don’t know can harm them… and their baby. It is well-known that medications used in the epidurals used today (and it’s also likely in the analgesia used during labor throughout the latter half of the 20th century would be similarly impactful, if not more so) suppresses many neonatal reflexes, thus preventing their ability to effectively nurse on the breast. Regardless, families are not counseled prenatally on the risks of pain management in labor and are instead expected to somehow achieve the presence of mind to be be legally capable of providing informed consent to these interventions while in the throes of labor—thus leaving the hospital free of accountability for profitable yet adversely impactful unnecessary birth interventions. The United States participated in drafting the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which was written over an 11-year period and adopted by the General Assembly of the UN in 1988. It was signed in the early 1990s by President Bill Clinton, but there was and has since been no move to ratify this declaration in the Senate. As of 2021, the United States is the only UN-participating country on earth to refuse ratification of this document. We did, however, ratify some of its optional additions to officially prohibit the sale of children and their participation in the military... Of course, these were already legally prohibited in this country, so their ratification was more of a political move than a logistical one. If the United States truly cared to protect its children, we would not be the only country left on earth which allows for prison terms of life without eligibility for parole of children found guilty of crimes (Human Rights Watch, 2005), as well as one of the only countries without any federal paid parental professional leave policy (Raub, et al., 2018), let alone one which subsidizes half the profits of an industry known for predatory marketing practices of substances which compromise the health and well-being of infants and their nursing parents. Contemporary U.S. Birthing Practices In 2016, a Cochrane Review was released criticizing the low levels of evidence on skin to skin research but recommending that it should be a regular practice regardless of whether the birth was vaginal or surgical for all healthy babies 35 weeks’ gestation and older (Moore, Bergman, Anderson & Medley,2016). The question begs to be asked, why did it take until 2016 for a practice which occurred naturally in births since the dawn of time to be formally recommended? Logic dictates that skin-to-skin contact and exclusive nursing are the biological norm for human babies, but scientific and policy perspectives dictate that practices must be proven safe and effective before they are endorsed by healthcare entities as opposed to there being documented risks which call the practice into question. It is impossible to have a thorough discussion of scientific recommendations for birth and feeding of human infants without addressing the proverbial elephant in the room, COVID-19. The public’s confidence in “science” and its myriad media controversies around conflicting public health and treatment recommendations are causing many families to stray to either side of the compliance spectrum; to blindly follow doctors’ orders, or to question their recommendations and choose their own treatment modalities. One under-discussed implication of the media discourse about public health is the impact on patients and families for non-compliance with medical recommendations in birth and infancy that they believe to be unnecessary or simply not worth the potential risks. The refusal of unwanted medical care in pregnant people can not only cause conflicts between the family and their medical providers but can also result in problematic referrals to law enforcement. These referrals are the violation of the right to medical privacy and can be immensely traumatic for the families. The dignity of risk and the right to choose to accept or refuse medical treatments is often disregarded when those in power determine that there is a risk to the fetus carried within the person in question, as some states specifically place the rights of the fetus over the rights of the parents. The refusal of vaginal exams during labor or a surgical birth may be reason enough, even in the absence of legal evidence or precedence, may be enough to trigger a lengthy legal battle that many families simply cannot afford to fight even though there has never been a law passed in any state that makes parents liable for their own pregnancy losses (Paltrow & Flavin, 2013). The Organization of the American States defines obstetric violence as when healthcare personnel provide “dehumanizing treatment [and] abusive medicalization and pathologization of natural processes,” which involves “a woman’s loss of autonomy and of the capacity to freely make her own decisions about her body… which has negative consequences for a woman’s quality of life (OAS & MESECVI, 2012). As Roberts (1997) purports, creating criminals out of these parents seems a far simpler solution than creating a system of healthcare that ensures healthy babies for all despite its lack of efficacy. Human Rights Violations for Families African American mothers, who are more likely to be single parents of low socioeconomic status considering the racially biased incarceration rates of African American men (Alexander, 2010) find themselves in a situation in which they’ve got a myriad of uphill battles that parents with financial and social privilege in this country may never consider at any point in their own postpartum experiences. Indeed, the vilification of brown-skinned people in the media and by the government serves to essentially kick these parents when they’re already down while simultaneously presenting the appearance of “supporting” them by offering meager government benefits so their children can receive a minimal level of health, comfort and education through various programs which may or may not be effective in their efforts. This effectively provides the government with a cover of plausible deniability in terms of the clear racial biases in policy that create these struggles in the first place, and in doing so, continue to ensure that today’s modern equivalent of the wealthy plantation owner continues to protect his assets off the backs of our nation’s most vulnerable. The widespread and legally acceptable domestic example of obstetric violence perpetrated against women of color is perhaps best represented by what became known as the “Mississippi Appendectomy” during the 1970s. During this time, poor black women frequently found themselves receiving hysterectomies without their informed consent (and sometimes without even knowing it was going to happen at all) when admitted to the hospital for birth, birth control such as a tubal ligation, or other gynecological procedures in order to provide practice for medical residents in conducting these procedures (Kugler, 2014). Aside from the obvious ethical concerns, there were financial incentives for physicians to continue this practice. Physicians were financially motivated by receiving more than triple the payment from Medicaid- an insurance provider known for paying very low premiums- for hysterectomies compared to the reimbursement for tubal ligations, thus encouraging them to perform this unnecessary procedure. Hysterectomy carries with it a 2000% increased risk of death compared to tubal ligation (Roberts, 1997). These racial biases that continue to be condoned within our healthcare and social welfare systems effectively violate a variety of human rights conventions, including Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, published in 1951. The United States maternal healthcare system inflicts conditions which in whole or in part bring about the physical destruction of members of a group as demonstrated by the dramatically increased maternal and infant mortality rates of parents and infants of color relative to those of white families. In performing medically unnecessary surgical births, the U.S. maternal healthcare system causes serious bodily or mental harm to them by way of forced medical procedures that increase the risk of future health complications up to and including death for both the parent and the child. The United States maternal healthcare system imposes measures intended to prevent births by way of forced administration of the birth control implant Norplant as a form of modern-day eugenics to prevent the number of children born into poverty that also specifically targeted black communities by allowing its use to be legally mandated for birthing people with substance abuse problems or as a condition of probation (Roberts, 1997). Finally, the Indian Adoption Project, a U.S. effort through the late 1950s and 1960s to remove indigenous children from their families on reservations and adopt them into white families to “assimilate them into mainstream society” (Lee, 2003) is but one example of a governmental effort to forcibly transfer the children of one group into the care of another group, the final act outlined as a form of genocide in article 2 of the UN convention (United Nations, 1951). While transracial and transcultural adoptions are no longer as blatantly wrong in the current day as they were in the mid-20th century, babies of color are disproportionately removed from their homes (Lee, 2003), and white families represent the majority of foster care providers thus continuing this rights-violating policy, albeit in a more subtle form. It would seem that legislators have learned a great deal from the abolition of slavery and its transformation into the modern-day penal system in that they have employed similar policy development to repackage sanctioned racial and cultural genocide as a desirable public service. Benefits of Medicalization or Risks from Deviating from the Biological Norm? The media often touts of the “benefits” physiologic birth, of skin-to-skin contact after the birth, and of breastfeeding. One could question whether this really means that these practices are known to be superior to the current medicalized standards of high-intervention births. What social justice measures have been taken to address the unnecessary harm that has come upon parents and infants because of medical personnel preventing them from attaining the basic human right to safely birth a baby according to the physiologic norm? Unfortunately, the answer to that question seems to be “very little.” In recent years, maternal mortality rates have risen sharply in the United States, from 12 deaths per 100,000 births to 19 (Macrotrends, 2022). Compared with 10 other developed nations, this places the US at the bottom of the barrel with the worst maternal mortality rate despite spending the most money on healthcare. Further, the United States is the only country that does not provide cost-free home healthcare after birth and to offer paid postpartum parental leave programs for working parents (Melillo, 2020). Surgical births represent a very large cohort within the United States, with rates varying from 22% to 35% of all births (CDC, 2021). The international healthcare community accepts that just 10-15% of cesareans will be medically necessary, and like the Twilight births of the 20th century, the high rates of surgical births like we have in the U.S. are widely considered unnecessarily risky for families (WHO, 2015). According to the CDC, 1996 was the year in which the total number of surgical births were at their lowest rates in quite some time (data provided was for the years 1989-2003), and VBAC, or vaginal birth after cesarean, was at the top of its bell curve with nearly 30 successes for every 100 VBAC attempts. After 1996, the rate of successful VBACs plummeted to just 10 out of every 100 attempts by 2003, while the number of cesarean births steadily rose annually (CDCa, N.D.). As of 2019, less than 14 of 100 VBAC attempts resulted in a vaginal delivery (CDCb, N.D.). If we are truly the wealthy and resourceful country we purport to be, why would rates of successful vaginal births after previous surgical births in recent years be roughly half of what they were 25 years ago? Infant mortality data are just as bleak, with the number of infant deaths reducing in recent years but at a rate much slower than comparable wealthy countries. The bulk of the infant deaths in the United States are in the southern states, where there are almost 9 deaths per 1000 births in the state of Mississippi—compared to Massachusetts’ rate of just under 4. There is a significant disparity of rate of death among Black non-Hispanic babies, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian or non-Hispanic Pacific Islander being dramatically higher than Hispanics, white non-Hispanic, or Asian non-Hispanic births (Kamal, Hudman, & McDermott, 2019). The well-known violent and insidious history of institutionalized and systemic racism is especially apparent with these numbers. Black families experience the highest mortality rates for their babies with just under 11 infants per 1,000 live births passing away within their first year of life. They additionally have the highest rates of preterm birth, and low birth weight, both of which are leading causes of infant mortality (Kamal, Hudman, & McDermott, 2019). The combined death rate for babies of Black or American Indian heritage is an astounding 15 deaths per 1000 births, more than triple that of white or Asian babies whose most common cause of death is bacterial infection (CDC, 2022). When the death rate of these infants of the two most socially and structurally oppressed racial groups within the United States is so much higher than the overall national average, it becomes clear that there is an undeniable and indisputable problem with perinatal healthcare delivery for these populations. Sanctioned Obstetric Violence A high-profile legal case of obstetric violence was brought in 1997 by a birthing parent against the hospital within which she was forced to undergo a surgical birth without her consent. The story of Laura Pemberton is but one case of the travesty of the medical system for women choosing to exercise their right to medical freedom of many. Unfortunately, there is not as much documentation of most of these births as there is with Ms. Pemberton’s. That she is a white Christian woman with apparent higher education is likely responsible for the increased media coverage of her case. The absence of legal precedent may have been a contributing factor to her losing her case against the Tallahassee Memorial Regional Medical Center for violating her constitutional rights and right to procedural due process as well as accusations of negligence and false imprisonment for a forced cesarean of her baby that she believed was not medically necessary. In 2007, Ms. Pemberton spoke at the National Summit to Ensure the Health and Humanity of Pregnant and Birthing Women held in Atlanta, Georgia. She closed her talk with the following powerful words: The judge said that my unborn baby was in control of the state and that it was the state’s responsibility to bring this unborn baby into the world safely... The judge already had his mind made up. The judge looked at me, pointed his finger at me, and said we are going to do this c-section and we are going to do it tonight. We had lost before we ever went into the room… I looked at the doctor… and I said to him, ‘You know that I’m fine, and you know that I can deliver this baby. I was prepped for surgery regardless. Again, they came and asked me to sign a consent form, which I refused. Just before the c-section was to begin, this doctor who had said that I could not do this naturally, he did one more exam while I was on the operating table. I was 9 centimeters dilated. My body was working, and yet they still had the right to remove my baby from my body against my will. Justice must and will be done. May God use me to see that no family ever has to endure the persecution that I have suffered. I have been raped by the system. (NAPW, 2009, 16:37) Ms. Pemberton’s obstetrician along with another obstetrician and the chairmen of the hospital’s obstetric staff “testified unequivocally that vaginal birth would pose a substantial risk of uterine rupture and resulting death of the baby (Pemberton v. Tallahassee Mem’l Reg’l Med. Ctr., Inc. (1999).” As it turns out, a large systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence regarding uterine rupture in vaginal births after “classical” cesareans where there is a vertical scar and “low transverse” cesareans (most commonly used today) where the incision is horizontal and low on the abdomen has been found to be less of a risk than Ms. Pemberton’s physicians purported. As of 2020, the evidence indicates that the classical vertical incision resulted in lower risk of organ injury than the transverse incisions in subsequent births, and that the incidence of uterine rupture in births following the vertical incisions was roughly 1% when there was not a trial of labor (TOL) (Moramarco, Korale Liyanage, Ninan, Mukerji & McDonald, 2020). This begs the question of why scientific research must validate the benefit and efficacy of practices that have been in place for the whole of human existence before they can be officially endorsed by medical professionals? Does this need not have the impact of claiming these practices as its own, like a proverbial flag on a mountaintop to claim ownership of land that is already home to an indigenous population? Have we not already gotten to a point in Euro-American historical wisdom to understand that this is unethical and immoral? Why does scientific inquiry get a “pass” for this behavior? What happened to the process of childbirth that brought forth a circumstance in which we must prove that the natural acts taken by humans for centuries are safe and effective enough to practice in hospital settings? Rights Violations for Breast/Chest Feeding Parents and Children When the United Nations drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, they made special note of the rights of birthing parents and children being subject to special care and consideration due to the vulnerable nature of these cohorts (United Nations, 1948). This declaration was further clarified in 2016 by the UN’s Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) to specifically state that the ability to breast/chest feed and the support of these actions is a matter of human rights—especially in the face of predatory marketing of artificial infant milks (OHCHR, 2016). In 1867, Henri Nestlé created his first infant formula, Farine Lactée. Shortly thereafter, competing companies followed in creating their own artificial infant milks. Within a hundred years of its creation, fewer than 20% of infants in the United States were receiving any breastmilk at all (Save the Children, 2018). During this time, quite a few laws were created to respond to erroneous and misleading marketing strategies (like actors dressed as medical personnel giving out samples in public parks and “teaching” families about the superiority of artificial infant milks relative to the milk made by human bodies for human babies. Through the 1970s, formula companies were providing gifts (colloquially known as bribes) for healthcare workers while encouraging the use of their products, and they donated formula to families in poor countries, offering “free” feeding advice to the public from salespeople disguised as nurses (Save the Children, 2018). Further, with more nursing parents in the United States entering a workforce that had not yet been fortified with policies to support on-the-job pumping of milk or family leave policies, feeding infants the parents’ own milk became more and more of a logistical challenge. Poor countries found their infants experienced a dramatic increase in death from malnutrition, pneumonia, and diarrhea after their widespread adoption of infant formulas (Stevens, 2009). Developed countries saw their formula-fed babies almost routinely admitted to the hospital in the summers for dehydration, and in the winter with respiratory illnesses (Bachrach. Schwartz & Bachrach, 2003; Howie, et al., 1990; Huang, et al., 2016). The problem of this predatory marketing had gotten so pervasive through the 1970s that in 1981, the World Health Organization created the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes that was voted for by 118 member-states. This code, sadly, provides only a recommendation and not a mandate of any form due to a variety of logistical and reality-based constrictions on its worldwide implementation. To date, the United States continues to have instated no legal measures to protect children’s health from predatory infant formula marketing campaigns (WHO, 2016). Conversely, the U.S. purchases an average of 50% of the formula sold annually in the United States to distribute free of charge to low-income families through our Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program (Kent, 2006). The WIC program was designed to support exclusive breastfeeding through the employ of International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants and an extensive network of peer breastfeeding counselors, some of whom receive a week of formal lactation education which leads to a Certified Lactation Counselor (CLC) credential, but many of whom have no formal lactation training. In the U.S., WIC peer breastfeeding counselors are the most attainable support for impoverished breastfeeding parents. Sadly, the racial disparity in advice given is tangible, with counselors more frequently giving breastfeeding advice to white women and bottle-feeding advice to black women (Beal, Kuhlthau & Perrin, 2003). It makes sense that the international board-certified lactation consultant would be a better support than a peer counselor, but unfortunately with such a relatively new worldwide credential there are a plethora of barriers to providing this level of specialized care. Geographic access and financial attainability are two of the biggest challenges for families, with families living within 15 miles of an IBCLC having higher rates of any breast/chest feeding than those in more rural areas (Haase, Brennan & Wagner, 2019). With the widespread acceptance of telehealth, this barrier is likely diminishing. The financial constraints, however, continue. Across 15 states in the U.S., no autonomous billing exists unless the IBCLC bills under another credential such as a MD, CNM, RN, etc. Myriad professionals and professional organizations such as the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine have unequivocally stated that insurance coverage for lactation services would improve breastfeeding care, however many still find themselves unable to afford this care in the absence of in-network insurance billing. Further, with 87.1% of U.S.-based IBCLCs being non-Hispanic and white (Mojab, 2015), there is an inevitable disparity in care both sought and received due to the plethora of socio-racial issues that are omnipresent within the U.S. Parents of Color are given formula and formula paraphernalia at higher rates by those charged with supporting optimal infant nutrition in birthing hospitals, given bottle feeding advice more frequently than white women, have more difficulty obtaining equitable lactation support, and are more likely to have legal involvement in their birthing and parenting practices than non-Hispanic white women. While one has the right to breast/chest feed their baby, they apparently do not have the right to obtain access to high-quality support to overcome feeding challenges- even those created and exacerbated by healthcare professionals. Through the ages, if a parent was unable to nurse their infant (or simply chose not to), a wet nurse would be utilized to feed their baby. While there is some ancient evidence of the use of bottles for infants, there is no evidence that bottle-feeding was the norm until much later in human history. Indeed, bottle nipples were once made of lead- a metal now known to be a strong neurotoxin and as such it may be presumed to have caused quite a few undiagnosed developmental and physical problems in infants. It is known and accepted that high-intervention births, such as surgical births utilizing general anesthesia for the parent or the use of synthetic hormones such as pitocin, can impede the ability to successfully nurse an infant due to the same disruption in hormones in the nursing parent, or due to the nervous system impacts these medications have on the infant during and after their birth. The high rates of birth intervention in the United States may well be one reason (despite the lack of research to support this assertion) for our low rate of exclusive breast/chest feeding success. One major factor in explaining the protective quality of nursing is to consider retrograde ductal flow. This is the two-way exchange that occurs between an infant’s saliva and their nursing parent’s nipple which allows for communication of the infant’s pathogen exposure that stimulates the production of antibodies within the parent’s milk ducts so that they can deliver the targeted antibodies back to the infant through nursing (Laouar, 2020). Of course, this is just one way (of a multitude) that nursing provides immunological support to infants, but it is perhaps the most timely given the current COVID-19 pandemic impacting all 8 billion humans on this planet. Birth/Feeding Colonialism and Existential Dilemmas UNICEF and the World Health Organization estimate that only around 40% of babies worldwide receive any breastmilk at all. In the United States, close to 90% of babies receive at least some breastmilk around the time of birth- which sounds positive at the outset- however by 6 months of age, only 15% of these babies are still receiving their parents’ milk (CDC, 2020b) . The highly populous state of New York has the highest rate of formula supplementation within the first 2 days of life; the practice of unnecessary formula supplementation of nursing infants is well-known to sabotage the successful breast/chest feeding relationship. The more scientific evidence we have that supports the “benefits” of natural processes such as physiologic birth and feeding and the less discussion there is around how these processes have been critical to the survival our species for millennia (as evidenced by our world population amounting to roughly 8 billion humans), the bigger the insult against indigenous, aboriginal, and native families- as well as others who do not fall into these demographics who simply want to trust in the wisdom their culture, and indeed their very humanity brings to childbirth and feeding. In low and middle-income countries throughout the world, 96% of children are breast/chest fed. The richest families in any country have the lowest breast/chest feeding rates, while the poorest tend to average 2 years of nursing worldwide (UNICEF, 2018). Just a third of babies born in my home state of New York were born in a hospital certified as Baby Friendly (CDC, 2020). Baby Friendly status is an optional certification that hospitals may seek indicating that they have policies and practices in place to support increased breast/chest feeding success for their patients, to increase the heath of not just nursing infants but their birthing parents as well. Almost 90% of families choose breast/chest feeding for their babies in NY, but just over half of those families are still breastfeeding at all by 6 months (CDC, 2017), with only a quarter of them breastfeeding without utilizing formula supplementation (CDC. 2020b). Only 40% of these babies continue to receive any breastmilk through their first birthday (CDC, 2020b). New York also has the highest rate of breastfed babies supplemented with infant formula prior to 2 days of age throughout the country (CDC, 2017). These statistics beg the question, why are treatments and procedures with clear inherent risks (such as surgical births that are not medically indicated, or the supplementation of infant feeding with unwanted infant formula) still practiced upon vulnerable populations without first obtaining their truly informed consent? Why are so many physicians allowed to recommend practices known to risk the lives and emotional well-being of their patients with impunity? Further, why must the scientific community prove equivocally that breastmilk is a complete food that doesn’t require maternal or infant vitamin supplementation in order to compete with the formula industry, especially with the imbalance of funding for such studies? And why are blood levels of nutrients like iron and vitamin d in nursing infants expected to be equivalent to an adult’s level of those same nutrients, especially when we have clear data that iron supplementation in early infancy (less than 6 months) brings with it a higher risk of viral illness? Or that there are no studies comparing vitamin d blood levels between vitamin supplementation and simple sun exposure? And why do peer-reviewed journals continue to accept and publish so many studies with methodological shortcomings or researcher bias which cast doubt upon the findings? What is their share of the responsibility for the perpetuation of these absurdities that practices which have been the biological imperative (physiologic unmedicated birth with the presence of any desired support people, continuous skin-to-skin contact, nonseparation of parent and infant and breast/chest feeding) since the dawn of humanity must now be empirically proven to be safe and effective before their acceptance into common practice, but denied equal research funding opportunities as the more financially lucrative birth and feeding interventions? And this leads to the question, what role does common sense play in scientific inquiry… how many studies do we need to prove that water is wet? How many hundreds or thousands of years of recorded history must we have to consider our biologically normal birthing and feeding practices to be optimal and intrinsically connected with physiologic safety and emotional well-being? The harm resulting from the widespread prevalence of birth and feeding interventions regarding infant and maternal mortality is known, but the impact of these practices upon the family dynamics is less widely understood as it is not directly researched. What we do know is that the term obstetric violence is starting to integrate into the common vernacular. The long-term emotional and societal implications of policies to criminalize motherhood has not been specifically explored adequately in the literature. What has been determined, however, is that the nonseparation of nuclear family units is psychologically ideal whenever it is possible and that poor families lack the same quantity and quality mental health and financial supports that are readily available to wealthy families. We know that families whose parents have clinically significant depression (i.e. that it indisputably impairs their ability to function) and those with clinically significant post-traumatic stress disorder (perhaps due to a traumatic birth experience) were found to be at a higher risk of experiencing child maltreatment than control groups (Muzik, et al., 2017). Breast/chest feeding success can decrease the risk and/or severity of postpartum mood disorders, and therefore can have a positive impact in reducing the risk of child maltreatment. Treatment for and prevention of these postpartum mood disorders by way of supporting safe physiologic birth and biological normal feeding practices would help mitigate the impact of these mood disorders on families from all walks of life (Choi, & Sikkema, 2016), but especially for families of marginalized communities. Parenting while poor and brown need not be a crime for citizens of one of the wealthiest countries on earth. The United Sates has some of the best medical and mental health treatments available on the planet. Families simply need access, and our medical institutions need common-sense healthcare policies that support biologic norms in birthing and feeding practices. Conclusion After all these hundreds of years after black Americans were supposedly freed from a life of forced servitude and 12+ generations of incomprehensible abuses beginning with their kidnapping from their homelands and continuing with the repeated rape and other types of forced reproduction, how can anyone of sound mind believe that the death of their babies at rates that are so much higher than any other demographic are remotely acceptable? While the battle for civil rights by black Americans and their allies received much media and governmental attention, the plight of the Indigenous may be far less loud and proud due to their depressingly dwindled numbers resulting from many hundreds of years of both blatant and clandestine policy geared towards their genocide, political silencing, and cultural erasure. The attempted whitewashing of history has failed to completely remove these atrocities from the U.S. history books. Much of the nation remains fully aware of the heinous actions taken by brazenly arrogant and dangerously ethnocentric European settlers against the indigenous inhabitants of Turtle Rock, one wonders what place common decency for our fellow humans may have in a modern society that largely continues to commemorate an infamous colonialist criminal such as Cristóbal Colón every year in October. Indeed, the plight of the indigenous remains relegated to the background to this day as the myriad struggles of their oppressed brothers and sisters of African descent take center stage in this post-George Floyd era where the Black Lives Matter movement has gathered international attention. Perhaps this is due to a necessary triaging of the issues to direct logistical efforts so that there may be some chance of success. Perhaps it is due to the sheer number of voices available to speak out against injustice that they are logistically restricted to unanimously battle against only the most recent travesty facing oppressed demographics while it remains present in the public eye via popular media. Perhaps since the widespread media coverage of the events at Standing Rock died out of the news publications and the murder of unarmed black Americans took center stage, the voices of reason and mutual loving respect needed to pivot to garner what success they could in response to tragedies happening too frequently to reasonably keep track of. At what point does the depravity of this healthcare system warrant an urgent call for action to address the problem and prevent the senseless deaths of so many babies? Why does the gratuitously complex bureaucratic nature of these systems continue to dictate an unchanging status quo in such a way that seems acceptable to so many that there don’t seem to be any large-scale calls to fundamentally change their structure to save so many lives lost? The true ratification of the human rights conventions outlined by the United Nations by the United States would necessitate an overhaul of well-established systems of power by powerful financial interests, and for this reason it does not seem that ratification will ever happen. It would take an overhaul not just of our current healthcare systems, but also of the financial-political processes that have been in place for generations; processes which only seem to be strengthening over time. Further, the systematic methods used to oppress and control people of color has been a part of the political and legislative structure of the United States since its founding and is intrinsically and irrevocably woven into the very fabric of our society. It is a very sad day for humanity when one realizes that the only way in which the protection of human rights for families may only be attainable after a complete redesign of the reactionary nature of the social health, public health, public safety, and fiduciary political policies. Socially, families need policies which offer professional and peer support options for birth and feeding such as birth and postpartum doulas (known to reduce the rate of traumatic births and improve postpartum parental and feeding self-efficacy). Further, our families need to be able to work with physicians that will not be allowed to let their implicit or explicit racial or cultural biases impact the quality of care they deliver. This would be a complex task, but it would also seem that hospitals already have quality assurance departments that ensure all of the medical billing criteria is impeccably documented, and the addition of another set of criteria to ensure there are no racial or social biases impacting care seems like a reasonable expectation when conducting patient file reviews. Public health policies should also mandate pre- and post-natal doula support, as the rates of surgical births decrease and the rate of successful breast/chest feeding increases with this type of support. A more humane family leave policy that is more in-line with other developed nations to protect workers from financial devastation and potential loss of employment is necessary to support the successful breast/chest feeding relationship as well as to support the emotional well-being of families. State or Federal Licensure of International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLCs) would help families be able to connect with a highly trained professional to help work through their feeding challenges and address the lack of insurance coverage for our nation’s Medicaid recipients. The war on drugs and the disproportionate incarceration of black men is directly responsible for needlessly tearing families apart in the United States, and amending this purported public safety policy to one of strategic mental health and substance abuse counseling in conjunction with social welfare policies to offer poor families a more humane and stable quality of life with equitable chances for obtaining an affordable higher education would be a good start toward achieving some level on the socioeconomic playing field for marginalized families. The need for restorative justice for families of color in this country is great and complex, but some baseline policies such as this would provide some better stability and prospects for many marginalized families so that the more complex social issues of institutionalized slavery and genocide can be navigated. Big businesses, their big tax breaks, and the subsequent financial lobbying power of these powerful interest groups would be a particularly complex challenge to dismantle. It seems clear given the history and state of the world that the financial interests of the medical, pharmaceutical, and infant formula companies have influenced the refusal to adopt and implement of the UN’s human (and child) rights conventions. These are multi-billion-dollar industries with powerful lobbyists who are strategically located around the periphery of every key legislative body worldwide. As they quietly finance the creation of an ever-increasing body of scientific evidence to show the efficacy of their products, the incremental reliance of the healthcare industry upon their products continues to increase accordingly, thus solidifying their position as key players within legislative efforts. A plan for overhauling the political structure to prevent corporate interests from swaying legislation and the structures for funding scientific research endeavors is beyond the scope of this paper, but this is the direction in which we need to go as a nation if we are to put the power back into the hands of the people and have widespread faith in the scientific research process once again. Our birthing parents are dying. Would-be birthing parents are being stripped of the right to get pregnant in the first place. Our babies, if they survive, are subjected to methods of feeding designed to earn profits at the expense of their health. While the United Sates does a terrible job of protecting the dignity and health of its citizens, it does a great job at oppressing and harming its minorities for profit in favor of perpetuating the socioeconomic privilege of the hegemony. If we are ever to truly protect the inalienable rights of the most vulnerable among us, there is no single policy change that can be proposed that may be a catalyst for change down the road. True change would require a complete overhaul of several key policy areas which support our entire socio-political system. One can hope that the “burn it all down and start over” method is not going to be what it takes for our society to become equitable and just, but in this point in history it is difficult to see how the logistic choreography necessary to make all the changes that need to be made can possibly be executed within the lifetime of anyone currently fortunate enough to survive their infancy. References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: New Press. Bachrach V.R., Schwarz E. & Bachrach L.R. (2003) Breastfeeding and the risk of hospitalization for respiratory disease in infancy: a meta‐analysis. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 157, 237–243. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/481276 Beal, A. C., Kuhlthau, K., & Perrin, J. M. (2003). Breastfeeding advice given to African American and white women by physicians and WIC counselors. Public health reports. 118(4), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/118.4.368 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2017). Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends and Maps. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpao_dtm/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DNPAO_DTM.ExploreByLocation&rdRequestForwarding=Form Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2021). Cesarean delivery by state. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/cesarean_births/cesareans.htm Centers for Disease Control (CDC)a. (2020). Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends and Maps. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control (CDC)a. (N.D.). QuickStats: Total and Primary Cesarean Rate and Vaginal Birth After Previous Cesarean (VBAC) Rate --- United States, 1989—2003. Centers for Disease Control (CDC)b. (2020). Breastfeeding Report Card. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm Centers for Disease Control (CDC)b. (N.D.). Births: Final Data for 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr70/nvsr70-02-508.pdf Choi, A., Kelsberg, G., & Safranek, S. (2010). Clinical inquiries. When should you treat tongue-tie in a newborn? The Journal Of Family Practice, 59(12), 712a-b. Cook-Lynn, E. (1996). Why I Can’t Read Wallace Stegner and Other Essays : A Tribal Voice. University of Wisconsin Press. Haase, B., Brennan, E., Wagner, C.L. (2019). Effectiveness of the IBCLC: Have we Made an Impact on the Care of Breastfeeding Families Over the Past Decade? Journal of Human Lactation. 35(3). 441-452. Retrieved from https://journals-sagepub-com.proxy.myunion.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177/0890334419851805 Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, et al, ‘Protective effect of breastfeeding against infection’, Br Med J, 1990, 300(6716).11–16. https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpao_dtm/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DNPAO_DTM.ExploreByLocation&rdRequestForwarding=Form Huang, C., Liu, W., Cai, J., Weschler, L.B et al., ‘Breastfeeding and timing of first dietary introduction in relation to childhood asthma, allergies, and airway diseases: a cross-sectional study’, J Asthma 2016, 54(5):488-497 Human Rights Watch. (2005). United States: Thousands of children sentenced to life without parole. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2005/10/11/united-states-thousands-children-sentenced-life-without-parole Kamal, R., Hudman, J., & McDermmott, D. (2019). What do we know about infant mortality in the U.S. and comparable countries? Health System Tracker. Retrieved from https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/infant-mortality-u-s-compare-countries/ Kaplan, L. (2012). Changes in childbirth in the United States. Frontispiece. 4(4). https://hekint.org/2017/01/27/changes-in-childbirth-in-the-united-states-1750-1950/ Kent, G. (2006). The high price of infant formulas in the United States. AgroFOOD Industry Hi Tech. 17(5). 21-23. http://www2.hawaii.edu/~kent/The%20High%20Price%20of%20Infant%20Formula%20in%20the%20US.pdf Kugler, S. (2014). Day 17: Mississippi appendectomies and reproductive justice. MSNBC. Retrieved from https://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/day-17-mississippi-appendectomies-msna293361 Laouar, A. (2020). Maternal Leukocytes and Infant Immune Programming during Breastfeeding. Trends in Immunology. (41)3. 225- 239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2020.01.005 League of Nations. (1924). Geneva declaration of the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://www.un-documents.net/gdrc1924.htm Lee, R.M. (2003). The transracial adoption paradox. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(6): 711–744. doi: https://dx-doi-org.proxy.myunion.edu/10.1177%2F0011000003258087 Leggitt, K. (2016). How has childbirth changed this century? Retrieved from https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/explore-healing-practices/holistic-pregnancy-childbirth/how-has-childbirth-changed-century# Macrotrends (2022). US Maternal Mortality Rate 2000-2022. Retrieved from https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/maternal-mortality-rate Melillo, G. (2020). US ranks worst in maternal care, mortality compared with 10 other developed nations. American Journal of Managed Care. https://www.ajmc.com/view/us-ranks-worst-in-maternal-care-mortality-compared-with-10-other-developed-nations Mojab, C.G. (2015). Pandora’s Box Is Already Open: Answering the Ongoing Call to Dismantle Institutional Oppression in the Field of Breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation. 31(1). 32-35 Moore, E.R., Bergman, N., Anderson, G.C., & Medley, N. (2016). Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Retrived from https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub4 Moramarco, V., Korale Liyanage, S., Ninan, K., Mukerji, A., & McDonald, S. D. (2020). Classical cesarean: What are the maternal and infant risks compared with low transverse cesarean in preterm birth, and subsequent uterine rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 42(2), 179–197. https://doi-org.proxy.myunion.edu/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.015 Muzik, M., Morelen, D., Hruschak, J., Rosenblum, K. L., Bocknek, E., & Beeghly, M. (2016). Psychopathology and parenting: An examination of perceived and observed parenting in mothers with depression and PTSD. Journal of affective disorders, 207, 242–250. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.035 National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW). (2009). Laura Pemberton [video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/4895023 Organization of American States (OAS) & Mechanism to Follow Up on the Implementation of the Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women (MESECVI). (2012). Second hemispheric report on the implementation of the belém do pará convention. Retrieved from https://www.oas.org/en/mesecvi/docs/mesecvi-segundoinformehemisferico-en.pdf Paltrow, L. & Flavin, J. (2013). Arrests of and Forced Interventions of Pregnant Women in the United States, 1973-2005: Implications for Women's Legal Status and Public Health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 38(2), 299-343. Pemberton v. Tallahassee Memorial Regional Medical Center, Inc. (1999). 66 F. Supp. 2d 1247. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=1839086537289754862&hl=en&as_sdt=6,33 Project Gutenberg. (2007). Project Gutenberg's the care and feeding of children, by L. Emmett Holt. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15484/15484-h/15484-h.htm#Cry Raub, A., Nandi, A., Earle, Al., De Guzman Chorny, N., Wong, E., Chung, P., Batra, P., Schickedanz, A., Bose, B., Jou, J., Franken, D., & Heymann, J. (2018). Paid parental leave: A detailed look at approaches across OECD countries. World Policy Analysis Center. Retrieved from https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD%20Report%20-%20Parental%20Leave%20OECD%20Country%20Approaches_0.pdf Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5402a5.htm Roberts, D. (1997). Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Pantheon Books. Sá Vieira, A.E., Torquato, C.N., Moraes Di, L.M., Maite, V., & Aparecida, S.I. (2016). Depressão pós-parto e autoeficácia materna para amamentar: prevalência e associação / Postpartum depression and maternal self-efficacy for breastfeeding: prevalence and association. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem, (6), 664. https://doi-org.proxy.myunion.edu/10.1590/1982-0194201600093 Save The Children. (2018). Don’t Push It: Why the formula industry must clean up its act. Retrieved from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/13218/pdf/dont-push-it.pdf Schack-Nielsen, L., Michaelsen, K.F. (2006). Breastfeeding and future health. Current Opinions in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 9(3). 289-96. doi: https://doi-org. 10.1097/01.mco.0000222114.84159.79. Shiel, W.C. (2018). What is twilight sleep in obstetrics? Retrieved from https://www.medicinenet.com/twilight_sleep_in_obstetrics/ask.htm Spock, B. (1946). Baby and Child Care. Retrieved from https://drspock.com/baby-childcare-10th-edition/ Stevens, E.E., Patrick, T.E., Pickler, R. (2009). A history of infant feeding. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 18(2). 32-39 Stube, A. (2009). The Risks of Not Breastfeeding for Mothers and Infants. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2(4). p 222-231. UNICEF. (2018). Breastfeeding-UNICEF Data- Child Statistics. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/180509_Breastfeeding.pdf United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR). (2016). Breastfeeding a matter of human rights, say UN experts, urging action on formula milk. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20904 United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf United Nations. (1951). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 78 U.N.T.S. 277, entered into force Jan. 12, 1951. Retrieved from http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/instree/x1cppcg.htm United Nations. (1959). Declaration of the rights of the child, G.A. res. 1386 (XIV), 14 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 19, U.N. Doc. A/4354. Retrieved from http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/instree/k1drc.htm United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child, res. 44/25, annex, 44 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 49) at 167, U.N. Doc. A/44/49 (1989), entered into force Sept. 2 1990.. Retrieved from http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/instree/k2crc.htm United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved from https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/crc/crc.html United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Division of Vital Statistics (DVS). (2022). Linked Birth / Infant Death Records 2017-2018, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. CDC WONDER On-line Database. Retrived from http://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current-expanded.html World Health Organization (2018). Breastfeeding. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/breastfeeding World Health Organization (WHO). (2015).WHO statement on cesarean section rates. Retrived from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/161442/WHO_RHR_15.02_eng.pdf;jsessionid=D7745DA5BCC3D2EE8CDBC337CCED20ED?sequence=1 Worldometer. (n.d.) World population by year. Retrieved from https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/world-population-by-year/

2 Comments

10/9/2022 03:44:39 pm

Pattern analysis that human city economy do. Section quite around back.

Reply

10/24/2022 08:55:21 pm

Enjoy leg child sign technology. Fast lawyer property focus natural pick value.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

HO*LIS*TIC ~ADJECTIVE: Relating to or concerned with complete systems rather than with individual parts

WNY Orofacial & Breastfeeding Support Center is a division of Holistic Parenting Network, LLC, located within the village of East Aurora, NY.

131 Orchard Park Rd. West Seneca, NY 14224 fax: (716) 508-3302 (716) 780-2662 [text friendly]

WNY Orofacial & Breastfeeding Support Center is a division of Holistic Parenting Network, LLC, located within the village of East Aurora, NY.

131 Orchard Park Rd. West Seneca, NY 14224 fax: (716) 508-3302 (716) 780-2662 [text friendly]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed